I’ve worked on Sales & Marketing teams for many large companies:

Sony Electronics

Prudential California Realty

Verizon

AT&T

Our commission split is good for you because we are a young company. You will be paid daily, in cash, based on your sales.

I’ve worked on Sales & Marketing teams for many large companies:

Sony Electronics

Prudential California Realty

Verizon

AT&T

Our commission split is good for you because we are a young company. You will be paid daily, in cash, based on your sales.

‘Soothing Tummy’ is on ebay!

https://www.ebay.com/itm/283269185701

—

#boostalive

#soothingtummy

Johns Hopkins Health Review

Spring/Summer 2016 Volume 3 Issue 1

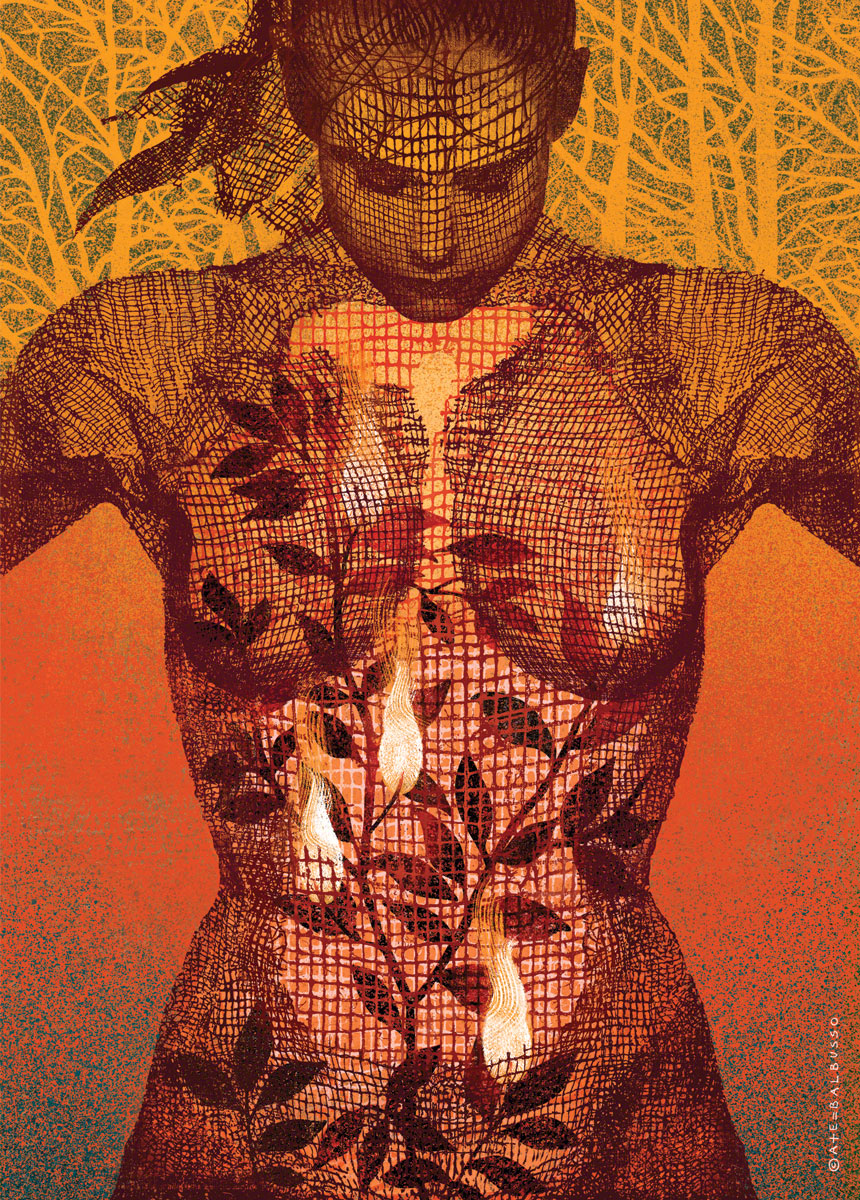

Understanding Inflammation

By Michael Anft

Inflammation has been found to be an underlying cause in many diseases, making it a hot topic in the health media. But what do we really know about chronic inflammation and its effects on the body?

As scientists have searched for the mysteries behind the diseases most likely to afflict us, they have alighted on one factor common to virtually all of them: inflammation. Chronic inflammation, headlines now regularly state, has a role in a host of common and often deadly diseases, including Alzheimer’s, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and possibly even depression.

Unsurprisingly, this news brings with it a raft of self-proclaimed remedies purporting to fight inflammation. Diets, herbs, supplements, and exercise regimens have flooded the market with promises to keep inflammation in check and improve overall health.

But is there evidence that over-the-counter products or sweeping lifestyle changes will reduce inflammation’s damaging effects? Scientists caution that despite its current high profile, inflammation remains a mystery. “Basic science hasn’t yet answered the major questions about inflammation,” says Michelle Petri, a rheumatologist and a director of the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. Researchers like Petri have been studying low-level inflammation as a culprit in a number of diseases for decades. What they have discovered has led to an emerging understanding of how lifestyle choices—like diet, dental health, and exercise—may influence inflammation and its potentially damaging downsides.

Inflammation is a vital part of the human immune system. When harmful bacteria or viruses enter your body, when you scrape or twist your knee, the body’s defense system kicks into high gear. Chemicals ramp up the body to fight, bathing the damaged area with blood, fluid, and proteins; creating swelling and heat to protect and repair damaged tissue; and setting the stage for healing.

Sentinel cells first alert the immune system to the presence of invaders. Another set of cells releases chemicals that signal the capillaries to leak blood plasma, which surrounds and slows down trespassers. Another group of sentinels, called macrophages, releases cytokines, which are specialized germ fighters. Immunizing B- and T-cells join in, destroying both the pathogens and the tissues they have damaged. Finally, a last wave of cytokines is released to end the job and signal the immune system that its work is done. Its mission completed, the immune system calls off its dogs.

When our body’s powers of correction go wrong, however, they can work against us. Think of the acute heat and swelling that protect us during a normal immune response—a fever, or the redness and pain that surround a new injury, for example—and you can get a hint of what chronic inflammation is. Unlike the inflammation that follows a sudden infection or injury, the chronic kind produces a steady, low level of inflammation within the body that can contribute to the development of disease. It’s the result, in part, of an overfiring immune system. Low levels of inflammation can get triggered in the body even when there’s no disease to fight or injury to heal, and sometimes the system can’t shut itself off. Arteries and organs break down under the pressure, leading to other diseases, including cancer and diabetes.

Scientists don’t fully understand how the immune system becomes short-circuited, but they have long known that some diseases, such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, emerge after the immune system has gone awry and attacked healthy tissue. Increasingly, as Americans and other Westerners live longer and get larger (35 percent of Americans are obese), researchers have also found that low-level immune responses triggered by extra weight and a lack of exercise can contribute to the development of other illnesses.

“For a long time, we had the idea that inflammation was involved in certain autoimmune diseases, but now we’re seeing this lower level of inflammation in people who are obese and people who are sedentary,” says Kimberly Gudzune, a physician at Johns Hopkins and a clinical researcher who focuses on obesity. “We see a link between obesity and some diagnostic markers for inflammation, but we don’t know what causes them. We worry that there’s something brewing for these people, that they are at higher risk for heart disease, cancer, and diabetes.”

Researchers have discovered that fat cells can trigger the release of a steady, low hum of cytokines that, in lieu of an invader to attack, go after healthy nerves, organs, or tissues. As we gain weight, the release becomes prolific, affecting our body’s ability to use insulin, sometimes leading to type 2 diabetes.

They have also learned that inflammatory cells can have an effect elsewhere in the body—for example, chronically infected and inflamed gums in the mouth can cause damage that leads to heart attack and stroke. And they know that inflammation contributes to congestive heart failure and uncontrolled hypertension, and that it somehow has a role in the tangled cells that are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers continue to find answers about how inflammation contributes to cancer. Inflammatory cells produce free radicals that destroy genetic material, including DNA, leading to mutations that cause cells to endlessly grow and divide. More immune cells are then called in, creating inflammation that feeds the growth of tumors.

The link between inflammation and cancer can sometimes be direct. When too much stomach acid—a feature of the immune system that evolved to fight foodborne bacteria—creeps up the esophagus, it causes inflammation and chronic heartburn. Extended exposure to this acid changes the nature of the cells lining the esophagus, increasing the risk of cancer.

In colon cancer patients, certain communities of bacteria associated with diarrhea can create cancer with help from inflammatory cytokines. Cells protected by mucus can become inflamed when that mucus wall is breached by bacteria, says Cynthia Sears, a doctor who specializes in infectious disease research at Johns Hopkins. “The lining in the colon makes peptides”—short chains of amino acids that act to protect the lining of the organ—“to thwart bacteria. If there aren’t enough peptides, bacteria can get a foothold, which means even more bacteria,” Sears says. As inflammation ramps up to fight it, so does the risk of cancer.

If inflammation is the behind-the-curtain factor in so many diseases, what can we do to keep it at bay? Researchers admit that they’re still figuring this out.

Petri has studied lupus for more than three decades and has been investigating the effects of chronic inflammation. “Lupus is basically friendly fire,” Petri explains. “We can’t get the immune system to calm itself down.”

Treating chronic inflammation, whether for lupus or other chronic ailments, is a challenge. Researchers have an idea that inflammation exists as part of a self-reinforcing loop system. If they could figure out how to interrupt or reverse one stage in that loop, then they might be able to develop drugs to stop it. But how do you tone down the immune response enough to control the inflammation but not so much that a body can’t fight disease? “We’ve done 20 to 25 years of clinical trials on lupus drugs,” Petri says, by way of example. “We’ve had maybe one success and 30 failures.”

Currently, there are no prescription drugs that specifically target chronic inflammation. (There are, of course, over-the-counter medications that treat the minor and temporary inflammation and accompanying pain caused by injuries or procedures, such as surgery. These are not meant to treat chronic inflammation.) Some drugs, such as hydroxychloroquine, once used to battle malaria, are useful in treating some lupus patients, but they don’t cure the disease. Aspirin and statins have shown promise in reducing inflammation in some people, but researchers aren’t sure how broadly useful such drugs are in that role. With the exception of far-from-perfect anti-inflammatory drugs, such as prednisone, a corticosteroid that brings with it a slew of side effects, scientists are still researching how best to contain inflammation. “We need something that can work broadly and quickly, and without a lot of side effects,” says Petri.

Finding a drug that both interrupts the immune cycle and maintains a healthy immune response is important not just for people battling illness but for all of us, because as we age, inflammation increases in the body. Scientists aren’t sure how and why, but interestingly, the study of HIV is offering some insight.

HIV triggers chronic inflammation in the body, even after medications have rendered levels of the virus undetectable in blood tests. Certain cytokines involved in that inflammation process can profoundly decrease testosterone levels, leading to muscle loss. “It’s possible that the chronic inflammation in people with HIV is similar to the chronic inflammation we see in aging,” says Todd Brown, an endocrinologist who researches the link between bodily markers for inflammation and chronic diseases found in people with HIV. If researchers can understand that process and create treatments to disrupt it in people with HIV, they could potentially translate their findings into treatments for similar muscle loss in aging.

Jeremy Walston is a Johns Hopkins geriatrician who investigates immune system response and muscle function in the elderly. He has been searching for markers that highlight the early signs of inflammation. Some blood tests for inflammation markers exist, but the researchers have uncovered two new markers that they believe may predict mortality and mark signs of late-in-life decline. “These are powerful inflammatory molecules that, when chronically expressed, lead to declines in stem cells and a remodulation of the immune system,” says Walston. “They also contribute to cell death,” particularly in the elderly, he says.

As the quest for diagnostic measures and therapies continues, researchers point to simple lifestyle measures we can all take to help prevent chronic inflammation. Scientists are skeptical of cure-all claims found in the new crop of anti-inflammation diet books, but they do recommend dropping pounds (and the harmful fat cells that come with obesity) and avoiding the now common American diet high in fats and sugars.

“Losing weight can have profound effects on lowering inflammation,” says Brown, who adds that eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables and low in fats, processed foods, and sugars is generally a good idea, though more study needs to be done to determine how it might affect inflammation. Exercising, which causes an acute inflammatory response in the short term, but an anti-inflammatory one when we regularly get moving, is another strong step to take, he adds.

Other researchers advise getting plenty of sleep, lowering stress levels, and seeking out treatment for inflammation-inducing culprits, such as gum disease and high cholesterol levels. Avoid contact with heavy metals such as mercury, which is found in dangerous amounts in some large fish, and limit exposure to substances, such as diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke, that can set off the immune system. Additional studies by Brown and his colleagues have also shown some advantage in increasing our intake of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D, though more research is needed.

Walston and others caution against popping dietary supplements touted as anti-inflammatory cures. Some so-called remedies, such as turmeric, taken in large amounts, may actually be toxic to the liver and other organs.

For most of us, keeping inflammation in check comes down to common sense basics: eat well, don’t smoke, get moving, get more rest, and see your doctor for regular physicals, which could help stop chronic inflammation before it becomes rampant. “All of the things our grandmothers told us were good for us are actually good for us,” says Brown. “Until we have a more nuanced understanding of what inflammation does, that’s what we have to fall back on.”

(https://www.johnshopkinshealthreview.com/issues/spring-summer-2016/articles/understanding-inflammation)